Most of us that have visited a family doctor are familiar with the drill: after taking a careful history and making a working diagnosis, your doctor scribbles down some words on a pad and hands it to you as your prescription. In human medicine, the next step is as intuitive as walking. Prescription in hand, you head over to the pharmacy, where you wait to have it filled and dispensed to you. Simple enough, right? So why is it that when you take your dog or cat to the vet, sometimes the vet provides the necessary medications and sometimes you’re sent to the nearest pharmacy? Can dogs and cats take the same medicines as people? If you’ve ever been confused by your pet’s prescriptions, this article is for you.

By law, certain drugs require a prescription in order to be sold to consumers. For example, if your veterinarian decides to treat your cat’s skin infection with antibiotics or manage your dog’s hypothyroidism with thyroid supplementation, a prescription is required.

Medications requiring a prescription from your veterinarian are not available at pet food stores or on the shelves at the local supermarket. The usage of such drugs needs to be monitored closely by the veterinary professional who decided they were medically necessary in the first place. So it should make sense that some medications are available only through veterinary clinics, or with their express permission.

It should come as no surprise that humans and animals are very different creatures indeed. While it is true that in many medical research settings, animal models are used to simulate human responses to medications and the like, animals and people are ‘built’ very differently. Anatomically and physiologically (that is, the way is which their bodies work), dogs and cats differ quite significantly from you or I. Their enzymes, needed to metabolize and break down foreign substances, such as pharmaceuticals, are different from ours. The best example that comes to mind is the issue of acetaminophen toxicity in cats. Although most people can manage taking acetaminophen with a minimum of life-threatening side effects, cats lack the necessary enzymes to break down this drug, causing toxic metabolites to accumulate in their bodies. Cats and dogs are not only different from people in their physiological make-up, but from each other as well. Insulin, for example, is metabolized at vastly different rates in cats versus dogs, such that insulin dosing regimes in diabetic cats is dramatically dissimilar to that used in diabetic canine patients.

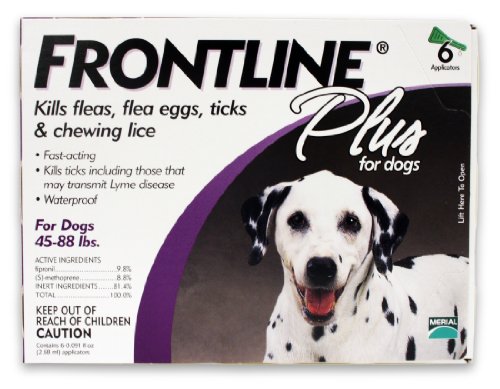

Having underscored the fact that pets and people are far from interchangeable from a pharmacological perspective, it becomes clearer that certain drugs are developed for use in animals only. Veterinary-exclusive medications come about for a variety of reasons. Some were developed because they treat conditions that do not exist in human medicine, such heartworm preventatives. Others were brought to the market as a veterinary variant of a known class of human medications. For example, NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) represent a family of drugs that are widely used in people for pain relief. Today, NSAIDs are also a mainstay of the veterinary pharmacy, but products prescribed are not necessarily interchangeable with their human counterparts. Veterinary pharmaceuticals may also be introduced to fill a dosing or drug-delivery niche: animals often require different strengths of medications than humans, or may not tolerate taking pills as often as people might.

When deciding on the right medical treatment for your pet, your veterinarian is forced to consider a number of factors as he or she reaches for the prescription pad. Firstly, and most importantly: does a veterinary product exist to treat this condition? If a pet-specific product is on the market, it is usually the gold standard of care. That drug’s effects in animals has been well characterized by its manufacturers; the vet doesn’t have to guess how a human drug will – or won’t – be tolerated in your pet. Remember, makers of human drugs aren’t counting on the fact that anyone other than a human will be using it, so they don’t concern themselves will potential side effects in other species. Interestingly, in some countries, it is not legal to substitute a human drug when a veterinary one already exists!

If a both a veterinary and human product exist, the first choice of the responsible veterinarian is the veterinary product, for the reasons outlined above. In addition, veterinary-exclusive drugs have the advantage of coming in pet-specific strengths and modes of administration. For example, a 10 kg dog, dosed by weight (as is customary), may need 5 mg of Drug X. Let’s say that the human form of Drug X only comes in 50 mg capsules, that can’t be split. In this case, the veterinary form of Drug X is the way to go, especially if it available in beef-flavoured tablets (which the human form is most likely not!). When there is no concern with strength or dosing, and your vet has already recommended a veterinary product (if it exists), some clients still prefer to go through a human pharmacy to have the prescription filled. Sometimes this is a decision based on cost, convenience, or availability. Two key points here: not all human products are cheaper than veterinary ones, and there is always an element of risk in giving medications to species in which they were not tested and for which they were not intended.

Your veterinarian may prescribe a treatment that does not exist commercially and needs to be compounded, either in-house or by a specialty compounding pharmacist. “Compounding” refers to the process combining at least two ingredients, one (or more) of which is a drug, to create an end-product in a form appropriate for dosing. Mixing an antibiotic powder with a tuna-flavoured, pharmaceutical-grade liquid to create a precise concentration of the medication in an animal-friendly form, is an example of compounding. The downside of this sometimes necessary practice is that it is considered an “off-label” use of commercially available pharmaceuticals, just as the use of human drugs for animals is. Drug manufacturers and Health Canada can only guarantee the efficacy and safety of drugs when they are in their original form; they can make no claims once the drug is mixed, or compounded, with other ingredients.

Pet prescriptions can be confusing, but it helps to know what factors are motivating your veterinarian’s choice of medication. Veterinarians are there to provide quality care for animals, but they are also there for you. The best defense against perplexing prescriptions is asking questions when they arise. Your vet will be only too happy to answer. Together, you can ensure your pet is receiving the medication that suits everyone’s needs.

By Rebecca Greenstein – Pets.ca writer

How Not To Use Treats In Dog Training

Treats are a valuable traini

How Not To Use Treats In Dog Training

Treats are a valuable traini

How To Treat Ticks On Dogs

About TicksKnowing about tic

How To Treat Ticks On Dogs

About TicksKnowing about tic

Mastiff Lovers & Dinosaur Poop!

Loving and Owning a MastiffG

Mastiff Lovers & Dinosaur Poop!

Loving and Owning a MastiffG

Dog Leash Training

A pet owner should always ta

Dog Leash Training

A pet owner should always ta

Why Dry Dog Food Is Bad For Dogs

Credit: Copyright of iStockphoto. All rights

Why Dry Dog Food Is Bad For Dogs

Credit: Copyright of iStockphoto. All rights

Copyright © 2005-2016 Pet Information All Rights Reserved

Contact us: www162date@outlook.com