Surasang (a table setting for a king)

Royal Cuisine � royal meal and royal table setting for celebratory occasions

What did kings in the Joseon Dynasty normally eat?

Meals prepared for kings are specifically called sura, and a table set with sura is called surasang (sang means a dining table in Korean).

Sura is not a word of Korean origin. It is a Mongolian term that was introduced in the late Goryeo Dynasty when Goryeo was the country of the Mongolian king's son-in-law. Surasang was served twice a day: at ten o'clock in the morning and at five o'clock in the evening. A light snack was served around two o'clock in the afternoon rather than lunch. Early in the morning, a bowl of porridge was served, and it was called chojoban (early breakfast).

King Gojong, who reigned in the late Joseon Dynasty from 1863-1907, did not drink any alcoholic beverages. Instead, he enjoyed ciders and sikhye (a sweet rice drink) as a light snack before going to bed. In winter, he enjoyed seolleongtang (beef broth with rice) and warm noodles. He especially liked noodles but since he didn't like spicy and salty foods, the cold noodles enjoyed by King Gojong were adorned with slices of boiled beef on top and slices of pear and pine nuts sprinkled around it. Pears were not sliced with a knife but shaved into thin slivers with a spoon. Rather than using beef broth, the noodles were added to water kimchi prepared with a lot of pears in it, which made the noodles taste especially sweet and refreshing.

King Sunjong, who reigned from 1907-1910, didn't have strong teeth or a strong stomach, which dampened his appetite.

King Sunjong enjoyed foods that were soft and not salty such as chadoljorigae (boiled-down meat balls) or hwangbokkkitang (soup prepared with diced beef). The Kkakdugi (a type of kimchi made with radish) favored by King Sunjong was sukkkakdugi, which is prepared with boiled radish.

Members of royal families did not share a table. Should there be two people dining together, they were served at separate tables and sat side by side. Three tables were prepared for each person: wonban, sowanban and chaeksangban.

At a meal prepared for a king, twelve different side dishes were served. However, the number of dishes actually placed on a table was much more. Additional dishes included two types of cooked rice (plain rice and rice mixed with red beans), two types of soups, three types of kimchi (cabbage kimchi, kkakdugi and water kimchi), two types of stew (bean paste stew and salted fish stew), three types of jang (soy sauce, seasoned soy sauce and seasoned chili paste) and one steamed dish. In principle, the ingredients and cooking methods should not overlap among dishes prepared for surasang.

The twelve side dishes, served on small plates, consisted of nine different dishes (cooked vegetables, fresh vegetables, chilled roasted meat or fish, boiled-down food, pickled vegetables, dried meat or fish, salted fish, pan-fried vegetables, and slices of boiled beef) and three special side dishes (poached eggs, sashimi, and warm roasted meat or fish).

The surasang of today has been handed down orally by royal servants and royal descendents of the late Joseon Dynasty; therefore, it may not be representative of the entire Joseon Period.

Literature on daily foods enjoyed in the royal court is much more scarce than that on banquet foods. The only literature that elaborates on royal daily foods is Wonhangeulmyojeongriuigwe (a record of protocols) (1795). According to its records, there were meals prepared with only seven or ten side dishes.

Taking an interest in citizens while within the royal court - the greater meaning of surasang

Preparing all these sumptuous foods for a single person in the royal court may appear absurd and wasteful; however, there was special meaning behind a meal prepared for a king. People would harvest crops, catch fish or hunt animals and present to their king only the finest quality foods appropriate for the current season.

The foods presented reflected the hard efforts of the people as well as their living conditions at the time. Therefore, when these foods were cooked and presented to the king, he was able to grasp the lives of his people and the seasonal conditions without roaming all over the nation.

Months of preparations for royal banquets

Being extravagant events, a large workforce had to be mobilized for royal banquets. Such banquets were held on special occasions such as sixtieth birthdays, fortieth birthdays, fiftieth birthdays, 41st birthdays and 51st birthdays of kings, queens or queen mothers, the bestowing of a new title, a king's admission to giroso (a home for the elderly), the formal designation of a crown prince, weddings, and receptions for foreign envoys. Banquets were categorized into jinyeon, jinchan, jinjak and sujak.

Once a royal sanction was obtained, a temporary office called jinyeondogam (an office for a royal banquet) was set up. The office would discuss procedures, purchase the required goods, and prepare activities, dancing and singing performances and foods for a banquet. These preparations took months. A daeryeongsuksu, a male cook specializing in banquet foods, would be invited to prepare the foods.

Banquet foods in periods after the mid-Joseon Dynasty are described in detail in jinchanuigwe (records of protocols for jinchan), jinyeonuigwe (records of protocols for jinyeon), deungrok (records of earlier events), and menus.

Currently, 27 different records of protocols and deungrok from the Joseon Dynasty have been preserved. Records of protocols for royal courts include a section on dishes served at the banquet, which describes the number of banquets held, the number and types of dishes served, and the number and types of flowers placed at the tables. Below the name of each dish, every ingredient and the amount used in cooking are documented in small lettering. These records of banquets also elaborate on all the items required for a banquet (lights, umbrellas, folding screens, floor cushions, tables, drinking cups, tablecloths, boxes for valuables, lanterns, vases, bamboo blinds, a thank you letter, etc.), musical instruments, dances, music and ceremonies.

At the center of a table placed before the king, tall piles of foods were stacked and their tops decorated extravagantly with flowers. This was called sangwha. The flowers used to adorn the foods were all made of paper. In royal courts, menus were called changan (proposed foods) or chanpumdanja (a list of dishes). Chanpumdanja was a scroll on which items or dishes served at a meal, whether a banquet or an everyday meal, were recorded. This was equivalent to a menu in the Western world, gondate in Japan, and chaidan in China.

Introduction To Of Some Lower Cholesterol Foodstuffs

Cholesterol is a fat-like element contained in the physique

Introduction To Of Some Lower Cholesterol Foodstuffs

Cholesterol is a fat-like element contained in the physique

The Simplest Way To Lessen Your High Cholesterol By Natural Means

High-cholesterol is a major variable inside the countrywide

The Simplest Way To Lessen Your High Cholesterol By Natural Means

High-cholesterol is a major variable inside the countrywide

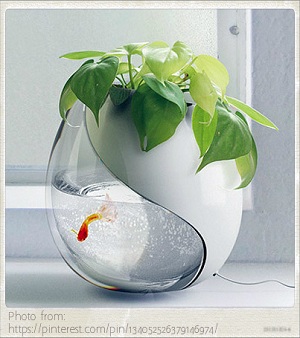

Starting Up An Aquaponics Set Up From See The Easy Way

Planting seeds in your aquaponics system can be a lot simpl

Starting Up An Aquaponics Set Up From See The Easy Way

Planting seeds in your aquaponics system can be a lot simpl