Cats, like humans, have an immune system that helps them to fight against a variety of diseases to stay healthy. The immune system includes various specialized cells, proteins, tissues, and organs which all work collectively to protect the body against foreign invaders, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi. Antibodies are proteins secreted by specific cells of the immune system, which bind to foreign substances, known as antigens, to destroy them. The immune system goes wrong when it mistakenly starts recognizing red blood cells (RBCs) as antigens or foreign elements and initiates their destruction. The hemolysis (destruction) of red blood cells results in the release of hemoglobin, which can lead to jaundice, and to anemia when the body cannot produce enough new red blood cells to replace the ones being destroyed. This disease is also known as immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, or IMHA. This disease is generally seen in cats within the age ranges of six months to nine years. At higher risk are domestic shorthair cats and male cats.

Your veterinarian will perform a detailed and complete physical examination, with laboratory tests, including complete blood tests, biochemical profile and urinalysis. These tests provide valuable information to your veterinarian for the preliminary diagnosis of the disease. More specific testing may be required to confirm the diagnosis and to find the underlying cause in case of secondary IMHA. X-ray images will be taken to evaluate the thorax and abdominal organs, including the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys. Echocardiography and ultrasound studies may be used in some animals. Your veterinarian will also take bone marrow samples for specific studies related to the development of RBCs.

In acute cases, IMHA can be a life-threatening condition requiring emergency treatment. In such cases your cat will be hospitalized. The primary treatment concern will be to stop the destruction of further RBCs and stabilize the patient. Blood transfusions may be required in cases where extensive bleeding or profound anemia is present. Fluid therapy is used to correct and maintain the body's fluid levels. In those cases that do not respond to medical treatment, your veterinarian may decide to remove the spleen to protect your cat from further complications. Your cat's progress will be monitored and emergency treatment continued until it is completely out of danger.

Strict cage rest may be required until your cat is stabilized. Some patients respond well, while for others long-term treatment is required; some cats may even require life-long treatment. After successful treatment, your veterinarian will schedule follow-up visits every week in the first month, and later, every month for six months. Laboratory testing will be performed at each visit to evaluate the status of the disease. If your veterinarian has recommended life-long treatment for your cat, 2‒3 visits per year may be required.

Paralysis-inducing Spinal Cord Disease in Cats

Myelopathy–Paresis/Paralysis in Cats

Myelop

Paralysis-inducing Spinal Cord Disease in Cats

Myelopathy–Paresis/Paralysis in Cats

Myelop

Cancerous and Non-Cancerous Growths in a Cat's Mouth

Oral Masses (Malignant and Benign) in Cats

An ora

Cancerous and Non-Cancerous Growths in a Cat's Mouth

Oral Masses (Malignant and Benign) in Cats

An ora

Pus Cavity Forming Under Tooth in Cats

Tooth Root (Apical) Abscess in Cats

Much like hum

Pus Cavity Forming Under Tooth in Cats

Tooth Root (Apical) Abscess in Cats

Much like hum

High Cholesterol in Cats

Hyperlipidemia in Cats

Hyperlipidemia is characte

High Cholesterol in Cats

Hyperlipidemia in Cats

Hyperlipidemia is characte

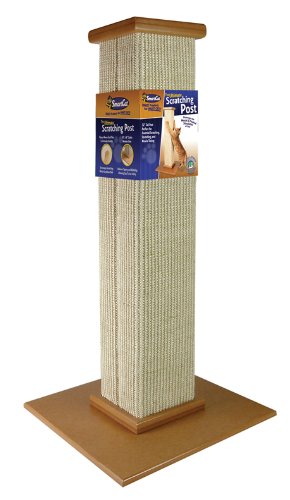

Selecting Your Perfect Cat Scratching Furniture

Having a cat is much like ha

Selecting Your Perfect Cat Scratching Furniture

Having a cat is much like ha

Copyright © 2005-2016 Pet Information All Rights Reserved

Contact us: www162date@outlook.com